Here's the first of the series:

Of course, there are a lot of details not covered in the video. So here I'm sharing further notes that touch on things I typically cover in the next several lessons (with varying amount of detail, depending on each student).

Rhythm is not actually the pulse itself. Rhythm is the relation of different events over time. We perceive different parts of the timing as separate events that we group (technical term is "chunk") in our minds. Each group has a mental focus or accent. At its core, accent just means anything that sticks out. When you say someone has an "accent", you're saying their manner of speaking sticks out, given whatever is common in those around them. Likewise, you can paint the trim in your house with an "accent color" to make it stick out.

Rhythmic relationships, i.e. groupings and accents, can exist without any real periodicity or regularity. Yet in the in the English-speaking world at least, most music has a regular beat that forms the backdrop against which rhythmic groups and accents are framed.

Most music not only has a steady beat but also has a regular accent. Every so many beats, there is extra conscious attention. This regular accenting is called meter.

So, in counting 1&2&3&4&, there are a lot of assumptions. This counting works for what is called duple meter where there are hierarchies of accents in pairs. Each number gets more focus than the &'s, and the numbers 1 and 3 are more accented than 2 and 4. The number 1 is the most accented of all.

Really, I'm only talking about metric accents. In lots of music, beats 2 and 4 or even the &'s can get accents of other sort. In other words, they can stick out in other ways. Any place in the meter can stick out loudly or have a noticeably long note or high pitch or unusual timbre (the sound quality that differentiates trumpet from violin).

Whenever any of these other accents do not match the regular metric accent, we experience syncopation. That means somewhere in our mind, we expect a certain regular focus point, but other things make an event stick out in a different place. The tension and complexity of syncopation is so fun and enjoyable that music without syncopation is almost never heard anymore. Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star has no syncopation, but you won't find any popular music today that isn't totally filled with syncopation.

For true beginners, getting comfortable with rhythm can be a complex process. Although my one rule is to keep moving, some rhythmic patterns are easier than others. If you make sound on the metric accents (i.e. on the down-strokes which are the numbered parts of the counting), it will be easier. If you play on an upstroke "&" but miss the nearby downstrums, it will feel syncopated. For some this is easy, for others, it takes some getting used to.

There are many good ways to practice:

Try putting on some music you like and just strumming along with muted strings so the chords don't clash. You can match rhythms in the recording or add your own cross rhythms to the mix.

One thing to note (this is a teaser for later rhythm lessons): overall patterns can be either straight (the upstroke "&" is right in the middle between each down strum) or swing (the upstroke is a little delayed and so is closer to the down strum that follows it, creating a strong up-DOWN… up-DOWN… up-DOWN feeling). Popular music uses both straight and swing rhythms but usually any particular song (or version of a song) is one or the other. Swing and straight rhythms are not usually mixed together.

Try planning specific rhythms and work on them in a loop until you feel comfortable. I've uploaded a simple rhythm writing chart you can use to write different patterns. I found that writing X for sound and O for miss works well. It's important that there is a symbol for the silent beats because that helps us focus on them even though they are silent.

Later, you can add other variations. You could use a / (slash) symbol to mean a real chord and mix that with silence and with muted strums. You could use a box to indicate a percussion slap on the guitar. You could play more on the thicker versus thinner strings. The options go on and on. Be creative.

|

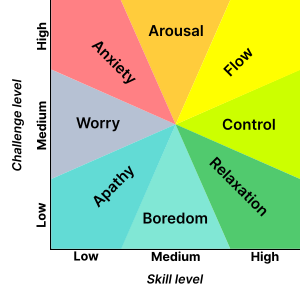

| note: Skill level is relative to yourself not to others. This is about finding whatever you do best and challenging yourself to go just a little further. |

the very end of the song and there is no song.

A beginner with the right attitude enjoying each discovery and musical experience has a better time than an advanced musician in one of the all-too-common bouts of wondering what the whole point is. The goal is to find the sense of flow where you challenge yourself just the right amount and got lost in the moment.

No comments:

Post a Comment